What is PIMS?

In April, doctors in the UK reported cases of serious illness in around twenty young patients, some of whom needed to be treated in intensive care.

The children had serious inflammation throughout their body. Inflammation is a normal response of the body’s immune system to fight infection. But sometimes the immune system can go into overdrive and begin to attack the whole body and if this happens, it is important that children receive urgent medical attention.

Doctors are concerned that in severe cases of PIMS the inflammation can spread to blood vessels (vasculitis), particularly those around the heart. If untreated, the inflammation can cause tissue damage, organ failure or even death,

Some of the symptoms of PIMS can overlap with other rare conditions, such as Kawasaki disease and Toxic Shock Syndrome. Some people have referred to the condition as ‘Kawasaki-like disease’. Like PIMS, complications from Kawasaki can cause damage to the heart. Kawasaki tends to affect children under five whereas PIMS seems to affect older children and teenagers.

Can PIMS be treated?

Yes. Doctors know what to look out for and will do tests to diagnose what’s wrong and what treatment to give the child. Even where doctors aren’t 100% sure whether a child or teenager has PIMS, they know how to treat the symptoms associated with it. Doctors use the same type of treatments to ‘reset’ the immune system for both PIMS and Kawasaki disease.

Researchers hope to find out more about how to diagnose patients as quickly as possible and which are the most suitable treatments for each patient.

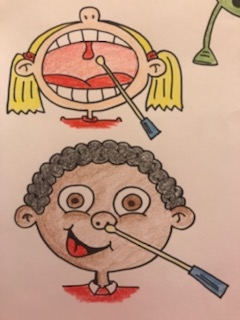

What symptoms should I look out for?

There’s a very wide range of symptoms and children with PIMS can be affected very differently. Some children may have a rash. Some, but not all, may have abdominal symptoms such as stomach ache, diarrhoea or being sick. All the children diagnosed with PIMS had a high temperature for more than three days, although this can be a symptom in many other illnesses and on its own is not a sign of PIMS.

While most won’t, some children may be severely affected by the syndrome. The most important thing is to remember that any child who is seriously unwell needs to be treated quickly – whatever the illness.The advice to parents remains the same: COVID-19 is extremely unlikely to make your child unwell; if you are worried about them, take a look at the red/amber/green symptom guide and if required, contact NHS 111 or your family doctor for urgent advice, or 999 in an emergency, and if a professional tells you to go to hospital, please go to hospital.

If your child doesn’t have these signs of being seriously unwell but you are still concerned, talk to you GP.

How many children have been affected?

It’s difficult to say because doctors are still in the process of reporting back – and also because there isn’t a definitive test. We think around 75-100 children may have been seriously affected and admitted to an intensive care unit. Almost all these children have since recovered.

A survey has been sent to 2,500 paediatricians (doctors who treat children) to gain a more complete picture of the condition. It asked doctors for details of every potential case seen since the beginning of March so we expect it to report a lot more cases – eg around 200 cases in England. But many of these children will not have been seriously ill and almost all children diagnosed with PIMS are now well again. The survey is likely to pick up cases which later turn out to be a different illness, eg Kawasaki disease. Some doctors believe a much large number of children may have had the condition but were very mildly affected and recovered without seeing a doctor.

Doctors have reported seeing a big reduction in cases in recent weeks but this could rise if cases of COVID-19 go up again.

Have any children died from PIMS?

We don’t know for sure because there isn’t a test for this condition. Doctors think two children may have died but they can’t be certain that there weren’t other reasons why the children died. These deaths are very sad indeed but doctors believe deaths in children related to PIMS are very, very rare. Many more children die of other infections such as flu or even chicken pox every year.

Is PIMS caused by COVID-19?

PIMS seems to be linked to COVID-19 because most of the children either had the virus or tested positive for antibodies indicating they had been infected (even if they hadn’t seemed ill at the time). But a very small number of the children with PIMS symptoms didn’t test positive for either.

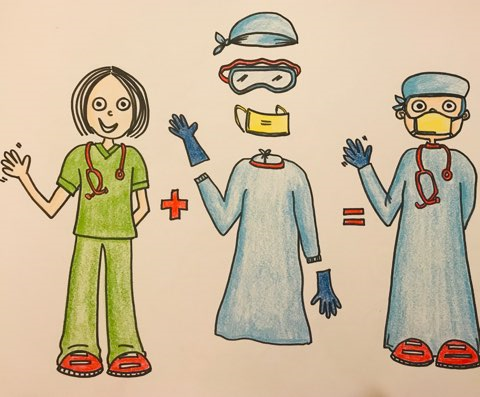

How can doctors tell if a child has PIMS?

There currently isn’t a test which will say whether a child definitely has the syndrome. A syndrome is a collection of many different symptoms which, together, can give doctors an indication of whether or not someone has a particular illness. Doctors will look for a pattern of symptoms relating to PIMS and then do more tests, such as blood pressure and blood analysis, to make a diagnosis. Researchers are currently trying to develop a blood test which can quickly indicate whether a child has PIMS.

Are black or Asian children more likely to be affected?

When the first few cases were identified in the UK there seemed to be a larger number of children from an Afro-Caribbean or Asian background. Doctors don’t yet know the reason for this and it may turn out that these children are not at a higher risk than other children – in some other countries where the syndrome has been written about the children were white. But it is important for families with these backgrounds to be aware of the signs and symptoms of the condition, however rare.

Doctors are learning more and more about this condition all the time and we hope to have more information over the next weeks and months. We will update our guidance regularly.

For more information, click here.